Incididunt nisi non nisi incididunt velit cillum magna commodo proident officia enim.

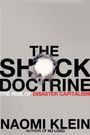

Naomi KLEIN

Naomi KLEIN[Boek van de Canadese schrijfster / onderzoeksjournaliste Naomi Klein. Ze is ook activiste voor de vrede en ageert tegen een neoliberaal dogmatisch kapitalisme in het algemeen en tegen de kritiekloze globalisering van het kapitalisme in het bijzonder.]

[Concreet laat ze zien hoe het neoliberale economische denken van Milton Friedman en de Chicago School de laatste 40 jaar is uitgepakt. Dat denken is dogmatisch over de vrije markt, over laissez faire, over een kleine overheid, en is daarmee uit op totale privatisering van de industrie en van maatschappelijke taken, op een bedrijfsleven dat niet belemmerd wordt, en op een afbraak van sociale voorzieningen. Ze toont aan dat het zijn kans kreeg in crisissituaties, vanaf de staatsgreep in Chili via die in Irak tot aan orkaan Katrina in de VS zelf. Met desastreuze resultaten, behalve voor een rijke elite.]

[Vandaar de term 'disaster capitalism': het bewust aangrijpen van catastrofes en rampen en de geslagenheid en ellende bij de betrokken burgers om de publieke sfeer af te breken in het voordeel van marktwerking en het private bedrijfsleven. Terwijl de term 'shock doctrine' slaat op de drievoudige schok die zoveel mensen de laatste veertig jaar hebben moeten doorstaan: de schok van een catastrofe, de schok daarna van keiharde neoliberaal kapitalistische maatregelen, en de letterlijke - vaak elektrische - schok wanneer je je daartegen verzette (denk aan de terreur en de foltering onder Pinochet in Chili en onder de andere junta's in Zuid-Amerika, de Abu Graibh-gevangenis in Irak, en zo verder. ]

[Het is een geweldig boek. Ik kan er hier niet genoeg over zeggen. Ik zal er een weblogstukje over schrijven. Het gevolg is wel dat ik erg veel meer citaten heb overgenomen dan ik normaal doe.]

De overstromingen van New Orleans en omgeving door de orkaan Katrina werden door Republikeinse politici, vastgoedmagnaten en door econoom Milton Friedman aangegrepen voor het 'met een schone lei beginnen' ('clean sheet') en het afbreken van sociale woningbouw, openbaar onderwijs, en andere sociale voorzieningen die tot dan toe door de overheid in stand waren gehouden. De catastrofe werd door die groepen aangegrepen ('big opportunities') om de meest dogmatische vorm van kapitalisme door te zetten waarin de overheid naar de achtergrond gedrongen werd en de markt en het bedrijfsleven hun gang konden gaan.

"One of those who saw opportunity in the floodwaters of New Orleans was Milton Friedman, grand guru of the movement for unfettered capitalism and the man credited with writing the rulebook for the contemporary, hypermobile global economy."(4)

"A network of right-wing think tanks seized on Friedman's proposal and descended on the city after the storm. The administration of George W. Bush backed up their plans with tens of millions of dollars to convert New Orleans schools into 'charter schools', publicly funded institutions run by private entities according to their own rules. Charter schools are deeply po larizing in the United States, and nowhere more than in New Orleans, where they are seen by many African-American parents as a way of reversing the gains of the civil rights movement, which guaranteed all children the same standard of education. For Milton Friedman, however, the entire concept of a state-run school system reeked of socialism. In his view, the state's sole functions were "to protect our freedom both from the enemies outside our gates and from our fellow-citizens: to preserve law and order, to enforce private contracts, to foster competitive markets." In other words, to supply the police and the soldiers —anything else, including providing free education, was an unfair interference in the market.

In sharp contrast to the glacial pace with which the levees were repaired and the electricity grid was brought back online, the auctioning off of New Orleans' school system took place with military speed and precision. Within nineteen months, with most of the city's poor residents still in exile, New Orleans' public school system had been almost completely replaced by privately run charter schools. Before Hurricane Katrina, the school board had run 123 public schools; now it ran just 4. Before that storm, there had been 77 charter schools in the city; now there were 31. New Orleans teachers used to be represented by a strong union; now the union's contract had been shredded, and its forty-seven hundred members had all been fired. Some of the younger teachers were rehired by the charters, at reduced salaries; most were not."(5)

Dit is wat Klein 'rampenkapitalisme' (disaster capitalism') noemt: het bewust aangrijpen van catastrofes en rampen en de geslagenheid en ellende bij de betrokken burgers om de publieke sfeer af te breken in het voordeel van marktwerking en private bedrijfsleven.

Die aanpak van 'economische shocktherapie' (door Klein de 'shockdoctrine' genoemd) in de lijn van Milton Friedman en de Chicago School (economisch denken waarin een ongehinderd kapitalisme centraal staat) bestaat al zo'n veertig jaar. Hij werd bijvoorbeeld gebruikt toen Pinochet in Chili aan de macht kwam na de coup - onder Amerikaanse invloed - waarin de Allende-regering werd afgezet (1973).

Friedman was adviseur van Pinochet. En veel economen in Chili uit de rijkere families - die onder Pinochet weer hun kans kregen - hadden aan de Chicago School hun opleiding gehad en dachten er dus precies hetzelfde over. Zoals later in New Orleans werden sociale voorzieningen afgebroken in het voordeel van het bedrijfsleven. Wie het er niet mee eens was werd simpelweg in de gevangenis gegooid of verdween. De shockdoctrine werd ook door andere oligarchische regimes gebruikt zoals in Sri Lanka (na de tsunami daar), (weer door de Amerikanen) in Irak, in Argentinië (ten tijde van de junta's in de 70-er jaren), Rusland, China, UK, Joegoslavië, en zo verder. En ook daar werd verzet met harde hand onderdrukt. Dezelfde aanpak werd gekoppeld aan steun door de WTO en het IMF. Uiteindelijk werd na de aanslagen van 11 september 2001 dezelfde doctrine in de USA doorgezet door de regering van Bush.

"The three trademark demands - privatization, government deregulation and deep cuts to social spending - tended to be extremely unpopular with citizens, but when the agreements were signed there was still at least the pretext of mutual consent between the governments doing the negotiating, as well as a consensus among the supposed experts. Now the same ideological program was being imposed via the most baldly coercive means possible: under foreign military occupation after an invasion, or immediately following a cataclysmic natural disaster. September 11 appeared to have provided Washington with the green light to stop asking countries if they wanted the U.S. version of 'free trade and democracy' and to start imposing it with Shock and Awe military force."(9)

"Seen through the lens of this doctrine, the past thirty-five years look very different. Some of the most infamous human rights violations of this era, which have tended to be viewed as sadistic acts carried out by antidemocratic regimes, were in fact either committed with the deliberate intent of terrorizing the public or actively harnessed to prepare the ground for the introduction of radical free-market 'reforms'."(9-10)

"Many of these countries were democracies, but the radical free-market transformations were not imposed democratically. Quite the opposite: as Friedman understood, the atmosphere of large-scale crisis provided the necessary pretext to overrule the expressed wishes of voters and to hand the country over to economic 'technocrats'."(10)

"To kick-start the disaster capitalism complex, the Bush administration outsourced, with no public debate, many of the most sensitive and core functions of government - from providing health care to soldiers, to interrogating prisoners, to gathering and 'data mining' information on all of us. The role of the government in this unending war is not that of an administrator managing a network of contractors but of a deep-pocketed venture capitalist, both providing its seed money for the complex's creation and becoming the biggest customer for its new services. "(12)

"Amid the weapons trade, the private soldiers, for-profit reconstruction and the homeland security industry, what has emerged as a result of the Bush administration's particular brand of post-September 11 shock therapy is a fully articulated new economy. It was built in the Bush era, but it now exists quite apart from any one administration and will remain entrenched until the corporate supremacist ideology that underpins it is identified, isolated and challenged. The complex is dominated by U.S. firms, but it is global, with British companies bringing their experience in ubiquitous security cameras, Israeli firms their expertise in building high-tech fences and walls, the Canadian lumber industry selling prefab houses that are several times more expensive than those produced locally, and so on."(14)

"In the attempt to relate the history of the ideological crusade that has culminated in the radical privatization of war and disaster, one problem recurs: the ideology is a shape-shifter, forever changing its name and switching identities. Friedman called himself a 'liberal', but his U.S. followers, who associated liberals with high taxes and hippies, tended to identify as 'conservatives', 'classical economists', 'free marketers', and, later, as believers in 'Reaganomics' or 'laissez-faire'. In most of the world, their orthodoxy is known as 'neoliberalism', but it is often called 'free trade' or simply 'globalization'.

Only since the mid-nineties has the intellectual movement, led by the right-wing think tanks with which Friedman had long associations - Heritage Foundation, Cato Institute and the American Enterprise Institute - called itself 'neoconservative', a worldview that has harnessed the full force of the U.S. military machine in the service of a corporate agenda. All these incarnations share a commitment to the policy trinity - the elimination of the public sphere, total liberation for corporations and skeletal social spending - but none of the various names for the ideology seem quite adequate.

Friedman framed his movement as an attempt to free the market from the state, but the real-world track record of what happens when his purist vision is realized is rather different. In every country where Chicago School policies have been applied over the past three decades, what has emerged is a powerful ruling alliance between a few very large corporations and a class of mostly wealthy politicians - with hazy and evershifting lines between the two groups.(...) Far from freeing the market from the state, these political and corporate elites have simply merged, trading favors to secure the right to appropriate precious resources previously held in the public domain ... (...)

A more accurate term for a system that erases the boundaries between Big Government and Big Business is not liberal, conservative or capitalist but corporatist. Its main characteristics are huge transfers of public wealth to private hands, often accompanied by exploding debt, an ever-widening chasm be tween the dazzling rich and the disposable poor and an aggressive nationalism that justifies bottomless spending on security. For those inside the bubble of extreme wealth created by such an arrangement, there can be no more profitable way to organize a society. But because of the obvious drawbacks for the vast majority of the population left outside the bubble, other features of the corporatist state tend to include aggressive surveillance (once again, with government and large corporations trading favors and contracts), mass incarceration, shrinking civil liberties and often, though not always, torture."(14-15)

"Any attempt to hold ideologies accountable for the crimes committed by their followers must be approached with a great deal of caution. It is too easy to assert that those with whom we disagree are not just wrong but tyrannical, fascist, genocidal. But it is also true that certain ideologies are a danger to the public and need to be identified as such. These are the closed, fundamentalist doctrines that cannot coexist with other belief systems; their followers deplore diversity and demand an absolute free hand to implement their perfect system. The world as it is must be erased to make way for their purist invention. Rooted in biblical fantasies of great floods and great fires, it is a logic that leads ineluctably toward violence. The ideologies that long for that impossible clean slate, which can be reached only through some kind of cataclysm, are the dangerous ones."(19)

"I am not arguing that all forms of market systems are inherently violent. It is eminently possible to have a market-based economy that requires no such brutality and demands no such ideological purity. A free market in consumer products can coexist with free public health care, with public schools, with a large segment of the economy—like a national oil company—held in state hands. It's equally possible to require corporations to pay decent wages, to respect the right of workers to form unions, and for governments to tax and redistribute wealth so that the sharp inequalities that mark the corporatist state are reduced. Markets need not be fundamentalist. Keynes proposed exactly that kind of mixed, regulated economy after the Great Depression, a revolution in public policy that created the New Deal and transformations like it around the world. It was exactly that system of compromises, checks and balances that Friedman's counterrevolution was launched to methodically dismantle in country after country. Seen in that light, the Chicago School strain of capitalism does indeed have something in common with other dangerous ideologies: the signature desire for unattainable purity, for a clean slate on which to build a reengineered model society."(20)

Ewen Cameron was een Amerikaans psychiater - werkzaam in Montreal, Canada, waar hij verbonden was aan het Allan Memorial Institute van de McGill University - die in de 1950er jaren in het geheim experimenteerde met electroshocks (ECT) en andere speciale verhoormethoden (drugs als LSD, etc.) bij zijn patiënten en waarvoor hij door de CIA en de Canadese regering betaald werd. Cameron was er van overtuigd dat hij bij zijn patiënten 'een schone lei' moest zien te bereiken voordat hij weer een gezonde persoonlijkheid kon opbouwen. Hij publiceerde daar ook gewoon over. Zijn patiënten kregen echter allen maar meer problemen en hij slaagdce er nooit in die gezonde persoonlijkheid op te bouwen dan wel die patiënten te genezen.

De Koude Oorlog woedde en de CIA was bijzonder geïnteresseerd in Cameron's methoden van 'mind control' en hersenspoeltechnieken. Het CIA-project kreeg achtereenvolgens namen als Project Bluebird, Project Artichoke, MKUltra. Tachtig instituten, waaronder 44 universiteiten en 12 ziekenhuizen, deden er aan mee. Waaronder dus de McGill University met Cameron.

"Like the free-market economists who are convinced that only a large-scale disaster - a great unmaking - can prepare the ground for their 'reforms', Cameron believed that by inflicting an array of shocks to the human brain, he could unmake and erase faulty minds, then rebuild new personalities on that ever-elusive clean slate."(29)

De CIA gebruikte de resultaten in het 'verhoor' van allerlei 'onwillige' gevangenen. Klein wijst er op dat de term 'marteling' ('torture') in alle stukken vermeden wordt en vervangen wordt door 'verhoortechnieken' en dergelijke. De CIA stelde er een heel handboek mee op (Kubark Counterintelligence Interrogation genoemd).

"The manual is dated 1963, the final year of the MKUltra program and two years after Cameron's CIA-funded experiments came to a close. The handbook claims that if the techniques are used properly, they will take a resistant source and "destroy his capacity for resistance". This, it turns out, was the true purpose of MKUltra: not to research brainwashing (that was a mere side project), but to design a scientifically based system for extracting information from 'resistant sources'. In other words, torture."(39)

"Though sanctioned by successive administrations in Washington, the U.S. role in these dirty wars had to be covert, for obvious reasons. Torture, whether physical or psychological, clearly violates the Geneva Conventions' blanket ban on 'any form of torture or cruelty', as well as the U.S. Army's own Uniform Code of Military Justice barring 'cruelty' and 'oppression' of prisoners."(42)

"That is what makes the Bush regime different: after the attacks of September 11, it dared to demand the right to torture without shame. That left the administration subject to criminal prosecution - a problem it dealt with by changing the laws."(43)

"Thousands of other prisoners being held in U.S.-run prisons - who, unlike Padilla, are not U.S. citizens - have been put through a similar torture regimen, with none of the public accountability of a civilian trial. Many languish in Guantánamo. Mamdouh Habib, an Australian who was incarcerated there, has said that "Guantánamo Bay is an experiment. . . and what they experiment in is brainwashing". Indeed, in the testimonies, reports and photographs that have come out of Guantánamo, it is as if the Allan Memorial Institute of the 1950s had been transported to Cuba. "(44)

"Disaster capitalists share this same inability to distinguish between destruction and creation, between hurting and healing."(47)

Over Milton Friedman en de Chicago School of Economics die ook in 1950-er jaren opkwamen. Men dacht daar over economie in termen van econmische natuurwetten, de balans van de markt, enz.

"Friedman's mission, like Cameron's, rested on a dream of reaching back to a state of 'natural' health, when all was in balance, before human interferences created distorting patterns. Where Cameron dreamed of returning the human mind to that pristine state, Friedman dreamed of depatterning societies, of returning them to a state of pure capitalism, cleansed of all interruptions - government regulations, trade barriers and entrenched interests. Also like Cameron, Friedman believed that when the economy is highly distorted, the only way to reach that prelapsarian state was to deliberately in flict painful shocks: only 'bitter medicine' could clear those distortions and bad patterns out of the way. Cameron used electricity to inflict his shocks; Friedman's tool of choice was policy - the shock treatment approach he urged on bold politicians for countries in distress. "(50)

Alleen moest Friedman 20 jaar wachten voordat hij zijn ideeën kon toepassen.

"Unable to test their theories in central banks and ministries of trade, Friedman and his colleagues had to settle for elaborate and ingenious mathematical equations and computer models mapped out in the basement workshops of the social sciences building. A love of numbers and systems is what had led Friedman to economics."(51)

"Like all fundamentalist faiths, Chicago School economics is, for its true believers, a closed loop. The starting premise is that the free market is a perfect scientific system, one in which individuals, acting on their own self-interested desires, create the maximum benefits for all. It follows ineluctably that if something is wrong within a free-market economy—high inflation or soaring unemployment—it has to be because the market is not truly free. There must be some interference, some distortion in the system. The Chicago solution is always the same: a stricter and more complete application of the fundamentals."(51)

"For this reason, Chicagoans did not see Marxism as their true enemy. The real source of the trouble was to be found in the ideas of the Keynesians in the United States, the social democrats in Europe and the developmentalists in what was then called the Third World. These were believers not in a Utopia but in a mixed economy, to Chicago eyes an ugly hodgepodge of capitalism for the manufacture and distribution of consumer products, socialism in education, state ownership for essentials like water services, and all kinds of laws designed to temper the extremes of capitalism. Like the religious fundamentalist who has a grudging respect for fundamentalists of other faiths and for avowed atheists but disdains the casual believer, the Chicagoans declared war on these mix-and-match economists. What they wanted was not a revolution exactly but a capitalist Reformation: a return to uncontaminated capitalism."(53)

Friedrich Hayek was Friedman's persoonlijke goeroe.

"By the 1950s, the developmentalists, like the Keynesians and social democrats in rich countries, were able to boast a series of impressive success stories. The most advanced laboratory of developmentalism was the southern tip of Latin America, known as the Southern Cone: Chile, Argentina, Uruguay and parts of Brazil. (...) Developmentalism was so staggeringly successful for a time that the Southern Cone of Latin America became a potent symbol for poor countries around the world: here was proof that with smart, practical policies, aggressively implemented, the class divide between the First and Third World could actually be closed. All this success for managed economies - in the Keynesian north and the developmentalist south - made for dark days at the University of Chicago's Economics Department."(55)

"For the heads of U.S. multinational corporations, contending with a distinctly less hospitable developing world and with stronger, more demanding unions at home, the postwar boom years were unsettling times. The economy was growing fast, enormous wealth was being created, but owners and shareholders were forced to redistribute a great deal of that wealth through corporate taxes and workers' salaries. Everyone was doing well, but with a return to the pre-New Deal rules, a few people could have been doing a lot better. The Keynesian revolution against laissez-faire was costing the corporate sector dearly. Clearly what was needed to regain lost ground was a counter revolution against Keynesianism, a return to a form of capitalism even less regulated than before the Depression. (...)

The enormous benefit of having corporate views funneled through academic, or quasi-academic, institutions not only kept the Chicago School flush with donations but, in short order, spawned the global network of right-wing think tanks that would churn out the counterrevolution's foot soldiers world wide."(56)

"Within the three-part formula of deregulation, privatization and cutbacks, Friedman had plenty of specifics. Taxes, when they must exist, should be low, and rich and poor should be taxed at the same flat rate. Corporations should be free to sell their products anywhere in the world, and governments should make no effort to protect local industries or local ownership. All prices, including the price of labor, should be determined by the market. There should be no minimum wage. For privatization, Friedman offered up health care, the post office, education, retirement pensions, even national parks. (...)

Though always cloaked in the language of math and science, Friedman's vision coincided precisely with the interests of large multinationals, which by nature hunger for vast new unregulated markets. In the first stage of capitalist expansion, that kind of ravenous growth was provided by colonialism - by 'discovering' new territories and grabbing land without paying for it, then extracting riches from the earth without compensating local populations. Friedman's war on the 'welfare state' and 'big government' held out the promise of a new font of rapid riches - only this time, rather than conquering new territory, the state itself would be the new frontier, its public services and assets auctioned off for far less than they were worth."(57)

Al in de 1950-er jaren kwam er een beweging op gang tegen het developmentalisme. Uiteraard intern van de kant van rijke grootgrondbezitters die macht en rijkdom moesten inleveren, maar ook extern van de kant van bedrijven die bv. in de ontwikkelingslanden in Zuid-Amerika niet meer hun gang konden gaan zoals voorheen. De angst voor het communisme werd misbruikt om een angst te creëren voor de ontwikkelingslanden. In de USA waren John Foster Dulles (Eisenhower's 'Secretary of State') en zijn broer Allen Dulles (hoofd CIA) op dat punt van invloed. Ze organiseerden coups in landen die ze wilden beïnvloeden (1953: Iran; 1954 - Guatemala; 1964 - Brazilië; 1965 - Indonesië).

Chili en andere landen werden aangepakt door vanaf 1956 educatieve beurzen te verlenen aan studenten uit die landen, zodat ze de Friedman-ideologie konden leren aan met name de Chicago School. Het project liep tot 1970 en werd mede betaald door Ford. Al gauw begonnen ze ook in eigen land economie-faculteiten te stichten waar die ideologie werd uitgedragen. Het werkte alleen niet zoals de conservatieven hoopten, omdat die jonge economen geen politieke invloed hadden in hun land.

"In the early sixties, the main economic debate in the Southern Cone was not about laissez-faire capitalism versus developmentalism but about how best to take developmentalism to the next stage. Marxists argued for extensive nationalization and radical land reforms; centrists argued that the key was greater economic cooperation among Latin American countries, with the goal of transforming the region into a powerful trading bloc to rival Europe and North America. At the polls and on the streets, the Southern Cone was surging to the left. "(62-63)

En nationalisatie van buitenlandse bedrijven - bv. de kopermijnen van Amerikaanse eigenaars in Chili - stond vaak op de agenda. Met name in Chili - waar Allende de verkiezingen van 1970 had gewonnen - was dat een mogelijkheid en ook het voornemen. Amerikaanse bedrijven (waaronder ITT die in Chili 70% had van de communicatie via telefoon etc.) besloten alles te doen om Chili economisch kapot te maken. Hin invloed op de regering van de USA (Kissinger, Nixon) was aanzienlijk. Dat alles werd in 1973 ontdekt en aan de kaak gesteld en het plan leed dus min of meer schipbreuk.

"Shortly after Allende was elected, his opponents inside Chile began to imitate the Indonesia approach with eerie precision. The Catholic University, home of the Chicago Boys, became ground zero for the creation of what the CIA called 'a coup climate'. Many students joined the fascist Patria y Libertad and goose-stepped through the streets in open imitation of Hitler Youth. In September 1971, a year into Allende's mandate, the top business leaders in Chile held an emergency meeting in the seaside city of Vina del Mar to develop a coherent regime-change strategy. According to Orlando Saenz, president of the National Association of Manufacturers (generously funded by the CIA and many of the same foreign multinationals doing their own plotting in Washington), the gathering decided that "Allende's government was incompatible with freedom in Chile and with the existence of private enterprise, and that the only way to avoid the end was to overthrow the government". The businessmen formed a 'war structure', one part of which would liaise with the military; another, according to Saenz, would "prepare specific alternative programs to government programs that would systematically be passed on to the Armed Forces"."(70)

"Their five-hundred-page bible - a detailed economic program that would guide the junta from its earliest days - came to be known in Chile as 'The Brick'. (...) Eight of the ten principal authors of 'The Brick' had studied economics at the University of Chicago."(71)

"Chile's coup, when it finally came, would feature three distinct forms of shock, a recipe that would be duplicated in neighboring countries and would reemerge, three decades later, in Iraq. The shock of the coup itself was immediately followed by two additional forms of shock. One was Milton Friedman's capitalist 'shock treatment', a technique in which hundreds of Latin American economists had by now been trained at the University of Chicago and its various franchise institutions. The other was Ewen Cameron's shock, drug and sensory deprivation research, now codified as torture techniques in the Kubark manual and disseminated through extensive CIA training programs for Latin American police and military."(71)

Meer details over de coup van 11 september 1973 in Chili en de wat er daarna gebeurde.

"In the years leading up to the coup, U.S. trainers, many from the CIA, had whipped the Chilean military into an anti-Communist frenzy, persuading them that socialists were de facto Russian spies, a force alien to Chilean society - a homegrown 'enemy within'. In fact, it was the military that had become the true domestic enemy, ready to turn its weapons on the population it was sworn to protect. (...) The generals knew that their hold on power depended on Chileans being truly terrified, as the people had been in Indonesia. In the days that followed, roughly 13,500 civilians were arrested, loaded onto trucks and imprisoned, according to a declassified CIA report."(76)

Het economische plan in 'The Brick' van de 'Chicago Boys' kon nu uitgevoerd gaan worden. En dat gebeurde vanaf de eerste dag na de coup. De Chicago Boys werkten daartoe intens samen met generaal Pinochet. De resultaten waren desastreus en niet de 'natuurlijke balans van economische krachten'.

"In 1974, inflation reached 375 percent - the highest rate in the world and almost twice the top level under Allende. The cost of basics such as bread went through the roof. At the same time, Chileans were being thrown out of work because Pinochet's experiment with 'free trade' was flooding the country with cheap imports. Local businesses were closing, unable to compete, unemployment hit record levels and hunger became rampant. The Chicago School's first laboratory was a debacle."(79-80)

"In that year and a half, many of the country's business elite had had their fill of the Chicago Boys' adventures in extreme capitalism. The only people benefiting were foreign companies and a small clique of financiers known as the 'piranhas', who were making a killing on speculation. The nuts-and-bolts manufacturers who had strongly supported the coup were getting wiped out. Orlando Saenz - the president of the National Association of Manufacturers, who had brought the Chicago Boys into the coup plot in the first place - declared the results of the experiment "one of the greatest failures of our economic history". The manufacturers hadn't wanted Allende's socialism but had liked a managed economy just fine. "(80)

" In March 1975, Milton Friedman and Arnold Harberger flew to Santiago at the invitation of a major bank to help save the experiment."(80)

De ideeën van de Chicago School werden nog extremer doorgezet. Chili belandde door Friedman's 'shock therapy' heel snel in een recessie: de economie kromp met 15%, de werkloosheid nam toe van 3 naar 20%. Dat 30 jaar later van 'het economisch wonder van Chili' gesproken werd zegt alles over de mythevorming onder bepaalde groepen. Het ging pas in de 1980-er jaren beter met Chili, maar juist omdat Pinochet door de slechte economie gedwongen was Friedman's uitgangspunten los te laten.

"The situation was so unstable that Pinochet was forced to do exactly what Allende had done: he nationalized many of these companies. In the face of the debacle, almost all the Chicago Boys lost their influential government posts, including Sergio de Castro. Several other Chicago graduates held prominent posts with the piranhas and came under investigation for fraud, stripping away the carefully cultivated facade of scientific neutrality so central to the Chicago Boy identity. The only thing that protected Chile from complete economic collapse in the early eighties was that Pinochet had never privatized Codelco, the state copper mine company nationalized by Allende. That one company generated 85 percent of Chile's export revenues, which meant that when the financial bubble burst, the state still had a steady source of funds."(85)

Het corporatisme - de samenwerking tussen een totalitair regime en een economische elite ten koste van arbeiders en het volk - was mislukt.

" By 1988, when the economy had stabilized and was growing rapidly, 45 percent of the population had fallen below the poverty line. The richest 10 percent of Chileans, however, had seen their incomes increase by 83 percent. Even in 2007, Chile remained one of the most unequal societies in the world - out of 123 countries in which the United Nations tracks inequality, Chile ranked 116th, making it the 8th most unequal country on the list. If that track record qualifies Chile as a miracle for Chicago school economists, perhaps shock treatment was never really about jolting the economy into health. Perhaps it was meant to do exactly what it did - hoover wealth up to the top and shock much of the middle class out of existence."(86)

"And that is why the financial world did not respond to the obvious contradictions of the Chile experiment by reassessing the basic assumptions of laissez-faire. Instead, it reacted with the junkie's logic: Where is the next fix?"(87)

Dat werden in de 1970-er jaren Brazilië, Uruguay, Argentinië.

"That meant that Argentina, Chile, Uruguay and Brazil - the countries that had been showcases of developmentalism - were now all run by U.S.-backed military governments and were living laboratories of Chicago School economics."(87)

De junta's voerden alle de economische maatregelen door die de Chicago School adviseerde met dezelfde slechte resultaten voor het volk. Terreur, verdwijningen, en martelingen - waarvan de methoden door Amerikanen / de CIA werden onderwezen - om elke oppositie de kop in te drukken waren dan ook aan de orde van de dag.

"Since those wanted by the various juntas often took refuge in neighboring countries, the regional governments collaborated with each other in the notorious Operation Condor. Under Condor, the intelligence agencies of the Southern Cone shared information about 'subversives' - aided by a state-of-the-art computer system provided by Washington - and then gave each other's agents safe passage to carry out cross-border kidnappings and torture, a system eerily resembling the CIA's 'extraordinary rendition' network today."(91)

"The exact number of people who went through the Southern Cone's torture machinery is impossible to calculate, but it is probably somewhere between 100,000 and 150,000, tens of thousands of them killed."(94)

Orlando Letelier was opgevoed in het denken van de Chicago School. Maar hij stapte daar van af toen hij - tijdens zijn werk als ambassadeur in Chili - zag wat de gevolgen waren. Omdat hij zijn kritiek ook uitsprak onder Pinochet werd hij er prompt gevangen gezet. Hij wist vrij te komen en vluchtte naar de VS terug.

"In 1976, Orlando Letelier was back in Washington, D.C., no longer as an ambassador but as an activist with a progressive think tank, the Institute for Policy Studies. Haunted by thoughts of the colleagues and friends still facing torture in junta camps, Letelier used his newly recovered freedom to expose Pinochet's crimes and to defend Allende's record against the CIA propaganda machine."(98)

Dat leidde wereldwijd weliswaar tot kritiek op het regime van Pinochet, maar niet op de economische shocktherapie die in Chili en in andere landen toegepast werd. In 1976 schreef hij over de relatie tussen die economische aanpak en de terreur die er mee gepaard ging. Nog geen maand later maakte een bom in zijn auto een eind aan zijn leven.

"An FBI investigation revealed that the bomb had been the work of Michael Townley, a senior member of Pinochet's secret police, later convicted in a U.S federal court for the crime. The assassins had been admitted to the country on false passports with the knowledge of the CIA."(99-100)

"Since the fall of Communism, free markets and free people have been packaged as a single ideology that claims to be humanity's best and only defense against repeating a history filled with mass graves, killing fields and torture chambers. Yet in the Southern Cone, the first place where the contemporary religion of unfettered free markets escaped from the basement workshops of the University of Chicago and was applied in the real world, it did not bring democracy; it was predicated on the overthrow of democracy in country after country. And it did not bring peace but required the systematic murder of tens of thousands and the torture of between 100,000 and 150,000 people."(102)

Er was simpelweg sprake van genocide op politieke tegenstanders, op iedereen met andere waarden en normen.

"By the sixties and early seventies in Latin America, the left was the dominant mass culture - it was the poetry of Pablo Neruda, the folk music of Victor Jara and Mercedes Sosa, the liberation theology of the Third World Priests, the emancipatory theater of Augusto Boal, the radical pedagogy of Paulo Freire, the revolutionary journalism of Eduardo Galeano and Walsh himself. It was legendary heroes and martyrs of past and recent history from José Gervasio Artigas to Simon Bolivar to Che Guevara. When the juntas set out to defy Allende's prophecy and pull up socialism by its roots, it was a declaration of war against this entire culture. (...) In Chile, Argentina and Uruguay, the juntas staged massive ideological cleanup operations, burning books by Freud, Marx and Neruda, closing hundreds of newspapers and magazines, occupying universities, banning strikes and political meetings."(104)

Ook het onderwijs werd gezuiverd, te beginnen met de professoren en leraren met andere dan Chicago School - ideeën over economie. En natuurlijk ook de vakbonden.

"Foreign corporations did more than thank the juntas for their fine work; some were active participants in the terror campaigns. In Brazil, several multinationals banded together and financed their own privatized torture squads. In mid-1969, just as the junta entered its most brutal phase, an extralegal police force was launched called Operation Bandeirantes, known as OBAN. Staffed with military officers, OBAN was funded, according to Brazil: Never Again, "by contributions from various multinational corporations, including Ford and General Motors". Because it was outside official military and police structures, OBAN enjoyed "flexibility and impunity with regard to interrogation methods", the report states, and quickly gained a reputation for unparalleled sadism.

It was in Argentina, however, that the involvement of Ford's local subsidiary with the terror apparatus was most overt. The company supplied cars to the military, and the green Ford Falcon sedan was the vehicle used for thousands of kidnappings and disappearances. (...)

While Ford supplied the junta with cars, the junta provided Ford with a service of its own —ridding the assembly lines of troublesome trade unionists."(108)

De kritiek op Friedman en de Chicago School groeide. Maar in 1976 kreeg Friedman desondanks de Nobelprijs voor economie.

"Friedman used his Nobel address to argue that economics was as rigorous and objective a scientific discipline as physics, chemistry and medicine, reliant on an impartial examination of the facts available. He conveniently ignored the fact that the central hypothesis for which he was receiving the prize was being graphically proven false by the breadlines, typhoid outbreaks and shuttered factories in Chile, the one regime ruthless enough to put his ideas into practice."(117-118)

Het jaar daarna kreeg Amnesty International de Nobel Vredesprijs voor zijn acties voor de mensenrechten in Chili etc. Het sugereerde weer eens dat het een (de economie) niets met het ander (een totalitair regime dat alle mensenrechten negeerde) te maken had.

"But by focusing purely on the crimes and not on the reasons behind them, the human rights movement also helped the Chicago School ideology to escape from its first bloody laboratory virtually unscathed."(118)

"Amnesty's position, emblematic of the human rights movement as a whole at that time, was that since human rights violations were a universal evil, wrong in and of themselves, it was not necessary to determine why abuses were taking place but to document them as meticulously and credibly as possible (...)

The narrow scope is most problematic in Amnesty International's 1976 report on Argentina, a breakthrough account of the junta's atrocities and worthy of its Nobel Prize. Yet for all its thoroughness, the report sheds no light on why the abuses were occurring. (...)

In another major omission, Amnesty presented the conflict as one restricted to the local military and the left-wing extremists. No other players are mentioned - not the U.S. government or the CIA; not local landowners; not multinational corporations. Without an examination of the larger plan to impose 'pure' capitalism on Latin America, and the powerful interests behind that project, the acts of sadism documented in the report made no sense at all - they were just random, free-floating bad events, drifting in the political ether, to be condemned by all people of conscience but impossible to understand."(119-120)

"Scrubbed clean of references to the rich and the poor, the weak and strong, the North and the South, this way of explaining the world, so popular in North America and Europe, simply asserted that everyone has the right to a fair trial and to be free from cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. It didn't ask why, it just asserted that."(121)

"The refusal to connect the apparatus of state terror to the ideological project it served is characteristic of almost all the human rights literature from this period. Although Amnesty's reticence can be understood as an attempt to remain impartial amid Cold War tensions, there was, for many other groups, another factor at play: money. By far the most significant source of funding for this work was the Ford Foundation, then the largest philanthropic organization in the world. In the sixties, the organization spent only a small portion of its budget on human rights, but in the seventies and eighties, the foundation spent a staggering $30 million on work devoted to human rights in Latin America. With these funds, the foundation backed Latin American groups like Chile's Peace Committee as well as new U.S.-based groups, including Americas Watch."(121)

Wat dus dezelfde organisatie is die de educatie van de Chicago Boys betaalde en de junta's op allerlei manieren - financieel en niet-financieel - steunde.

"In the Southern Cone, the contradictions were surreal: the philanthropic legacy of the very company most intimately associated with the terror apparatus - accused of having a secret torture facility on its property and of helping to disappear its own workers - was the best, and often the only, chance of putting an end to the worst of the abuses. Through its funding of human rights campaigners, the Ford Foundation saved many lives in those years. And it deserves at least part of the credit for persuading the U.S. Congress to cut military support to Argentina and Chile, gradually forcing the juntas of the Southern Cone to scale back the most brutal of their repressive tactics. But when Ford rode to the rescue, its assistance came at a price, and that price was - consciously or not - the intellectual honesty of the human rights movement. The foundation's decision to get involved in human rights but "not get involved in politics" created a context in which it was all but impossible to ask the question underlying the violence it was documenting: Why was it happening, in whose interests?"(124)

"The widespread abuse of prisoners is a virtually foolproof indication that politicians are trying to impose a system - whether political, religious or economic - that is rejected by large numbers of the people they are ruling."(125)

"The Chicago Boys' first adventure in the seventies should have served as a warning to humanity: theirs are dangerous ideas. By failing to hold the ideology accountable for the crimes committed in its first laboratory, this subculture of unrepentant ideologues was given immunity, freed to scour the world for its next conquest. These days, we are once again living in an era of corporatist massacres, with countries suffering tremendous military violence alongside organized attempts to remake them into model 'free market' economies; disappearances and torture are back with a vengeance. And once again the goals of building free markets, and the need for such brutality, are treated as entirely unrelated."(127-128)

Over de Britse premier Thatcher die het goed kon vinden met Hayek - de mentor van Friedman en Pinochet. Maar ze was niet populair, haar economische resultaten waren slecht, en de verkiezingen kwamen er aan. Ze kon - met andere woorden - op dat moment geen neoliberale, Friedmaniaanse aanpak doorzetten in de UK, al zou ze - met haar ideeën over een maatschappij van eigenaars - wel willen. Ze kreeg haar kans toen Argentinië op 2 april 1982 de Falkland-eilanden bezette.

"sessment. The Southern Cone's experiment had generated such spectacular profits, albeit for a small number of players, that there was tremendous appetite from increasingly global multinationals for new frontiers—and not just in developing countries but in rich ones in the West too, where states controlled even more lucrative assets that could be run as for-profit interests: phones, airlines, television airwaves, power companies. If anyone could have championed this agenda in the wealthy world, it would surely have been either Thatcher in England or the American president at the time, Ronald Reagan."(132)

"Nixon's tenure was a stark lesson for Friedman. The University of Chicago professor had built a movement on the equation of capitalism and freedom, yet free people just didn't seem to vote for politicians who followed his advice. Worse, dictatorships - where freedom was markedly absent - were the only governments who were ready to put pure free-market doctrine into practice. So while they griped about being betrayed at home, Chicago School luminaries junta-hopped their way through the seventies. Almost everywhere that right-wing military dictatorships were in power, the University of Chicago's presence could be felt. (...) Indeed, in the early eighties, there was not a single case of a multiparty democracy going full-tilt free market."(133-134)

"Across the Atlantic, Thatcher was attempting an English version of Friedmanism by championing what has become known as 'the ownership society'."(135)

Intussen kregen allerlei autoritaire regimes het in de 1980-er jaren moeilijk (Iran, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia), wat de kansen voor het neoliberalisme / de Chicago School - aanpak een stuk kleiner maakte.

"From a military standpoint, the eleven-week battle [de Falkland-oorlog] appears to have almost no historic significance. Overlooked, however, was the war's impact on the free-market project, which was enormous: it was the Falklands War that gave Thatcher the political cover she needed to bring a program of radical capitalist transformation to a Western liberal democracy for the first time."(137)

"Thatcher used the enormous popularity afforded her by the victory to launch the very corporatist revolution she had told Hayek was impossible before the war. When the coal miners went on strike in 1984, Thatcher cast the standoff as a continuation of the war with Argentina, calling for similarly brutal resolve."(138)

"In Britain, Thatcher parlayed her victory in the Falklands and over the miners into a major leap forward for her radical economic agenda. Between 1984 and 1988, the government privatized, among others, British Telecom, British Gas, British Airways, British Airport Authority and British Steel, while it sold its shares in British Petroleum."(139)

Vanaf dat moment werd de 'crisishypothese' in de Chicago School populair. Je hoefde geen coup te hebben om neoliberale ideeen door te zetten, als er maar sprake was van een immense crisis die grote delen van de bevolking raakte en onzeker maakte. De kunst was om er klaar voor te zijn.

"They [Chicago School-mensen] painstakingly built up a new network of right-wing think tanks, including Heritage and Cato, and produced the most significant vehicle to disseminate Friedman's views, the ten-part PBS miniseries Free to Choose - underwritten by some of the largest corporations in the world, including Getty Oil, Firestone Tire & Rubber Co., PepsiCo, General Motors, Bechtel and General Mills. When the next crisis hit, Friedman was determined that it would be his Chicago Boys who would be the ones ready with their ideas and their solutions."(141)

Over de economische crisis in Bolivia van 1985 waarbij advies gevraagd werd aan Harvard-econoom Jeffrey Sachs.

"Although Sachs shared Keynes's belief in the power of economics to fight poverty, he was also a product of Reagan's America, which was, in 1985, in the midst of a Friedman-inspired backlash against all that Keynes represented. Chicago School precepts about the supremacy of the free market had rapidly become the unquestioned orthodoxy in Ivy League economics departments, including Harvard's, and Sachs was definitely not immune. "(144)

Tegen de wensen van de kiezers in en zelfs onbekend voor zijn kabinet werd door Pax samen met anderen in het geheim een economische shocktherapie in de lijn van het neoliberalisme uitgewerkt (het document D.S. 21060 bevatte een immens groot aantal van 220 nieuwe wetten die ineens zouden moeten worden ingevoerd). Het kabinet werd gepaaid met de toegezegde financiële ondersteuning door de VS als de plannen werden doorgezet. De plannen werden doorgezet. De economische resultaten waren desastreus voor het grootste deel van de bevolking, maar niet voor de kleine groep van rijken.

"One immediate result of this resolve [dat de neoliberale plannen ondanks de slechte resultaten werden doorgezet, naar het advies van Sachs] was that many of Bolivia's desperately poor were pushed to become coca growers, because it paid roughly ten times as much as other crops (somewhat of an irony since the original economic crisis was set off by the U.S.-funded siege on the coca farmers.) "(150)

Allerlei tijdschriften als The Economist waren kritiekloos enthousiast over wat Sachs bereikt zou hebben, en zo verder. Bolivia werd - met voorbijgaan aan alle feiten - beschreven als een succesverhaal van wat de vrije markt kon opleveren, als het eerste voorbeeld waarbij neoliberalisering niet samenging 'met de bajonet' maar democratie.

[Er zijn inderdaad twee constanten die steeds weer terugkomen: het op een volkomen onterechte manier gebruiken van de metafoor ziekte, therapie, en zo verder. En de kritiekloze juichpartijen van de belangrijke - waarschijnlijk Amerikaanse - media over het neoliberalisme waarin de ellende van het volk geen plaats heeft en alle aandacht uitgaat naar de rijke elite die als enige profiteert van die vrije markt.]

"'Bolivia's Miracle' gave Sachs immediate star status in powerful financial circles and launched his career as the leading expert on crisis-struck economies, sending him on to Argentina, Peru, Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela in the coming years."(151)

"The story of the Bolivian miracle has been told and retold, in newspaper and magazine articles, in profiles of Sachs, in Sachs's own best-selling book, and in documentary productions such as PBS's three-part series Commanding Heights: The Battle for the World Economy. There is one major problem: it isn't true. Bolivia did show that shock therapy could be imposed in a country that had just had elections, but it did not show that it could be imposed democratically or without repression - in fact, it proved, once again, that the opposite was still the case."(152)

Sterker nog: de 'bajonet' was as wel degelijk - wanneer er protesten kwamen werd de staat van beleg afgekondigd, werden mensen tijdelijk ontvoerd, werd op die manier chantage gepleegd, en zo verder. Het ging minder gepaard met terreur en foltering dan voorheen onder de Zuid-Amerikaanse regimes, maar je kunt toch moeilijk volhouden dat alles verliep met democratische instemming: de repressie was groot.

"In this way, Bolivia provided a blueprint for a new, more palatable kind of authoritarianism, a civilian coup d'éétat, one carried out by politicians and economists in business suits rather than soldiers in military uniforms - all unfolding within the official shell of a democratic regime."(154)

Crises - als de hyperinflatie in Bolivia - konden dus aangegrepen worden om draconische economische maatregelen door te drukken.

"There was no shortage of such opportunities in the eighties. In fact, much of the developing world, but particularly Latin America, was at that very moment spiraling into hyperinflation. The crisis was the result of two main factors, both with roots in Washington financial institutions. The first was their insistence on passing on illegitimate debts accumulated under dictatorships to new democracies. The second was the Friedman-inspired decision at the U.S. Federal Reserve to allow interest rates to soar, which massively increased the size of those debts overnight."(156)

In Zuid-Amerikaanse landen bijvoorbeeld hadden de junta's hun nationale schulden bij IMF, World Bank, VS-banken enorm verhoogd, om wapens te kopen, om het leger en de politie uit te breiden, om prestige-objecten te bouwen, om zichzelf en vriendjes te verrijken, en zo verder (Argentinië: van $7.9 miljard naar $45 miljard; Uruguay: $0,5 miljard naar $5 miljard; Brazilië van $3 miljard naar $103 miljard). Uit transcripties van officiële gesprekken (bv. met Kissinger) is gebleken dat men in de VS heel goed op de hoogte was van waar al dat geld naar toe ging (vaak naar Zwitserse bankrekeningen en zo). Desondanks stelden ze daar de eis dat de nieuwe democratische regeringen van die landen de nationale schulden moesten aflossen.

"At the time of the transitions to democracy, powerful arguments were made, both moral and legal, that these debts were 'odious' and that newly liberated people should not be forced to pay the bills of their oppressors and tormentors. The case was especially strong in the Southern Cone because so much of the foreign credit had gone straight to the military and police during the dictatorship years - to pay for guns, water cannons and state-of-the-art torture camps."(157)

"The remainder of the national debt was mostly spent on interest pay ments, as well as shady bailouts for private firms. In 1982, just before Argentina's dictatorship collapsed, the junta did one last favor for the corporate sector. Domingo Cavallo, president of Argentina's central bank, announced that the state would absorb the debts of large multinational and domestic firms that had, like Chile's piranhas, borrowed themselves to the verge of bankruptcy. The tidy arrangement meant that these companies continued to own their assests and profits, but the public had to pay off between $15 and $20 billion of their debts; among the companies to receive this generous treatment were Ford Motor Argentina, Chase Manhattan, Citibank, IBM and Mercedes-Benz. (...) The transcript proves that the U.S. government approved loans to the junta knowing they were being used in the midst of a campaign of terror. In the early eighties, it was these odious debts that Washington insisted Argentina's new democratic government had to repay."(158)

Een ander element van schok ontstond toen voorzitter Volcker van de Amerikaanse Federal Reserve de rentepercentages op leningen ongelimiteerd liet stijgen. Dat leidde in de VS zelf tot allerlei faillisementen, maar werd nog eens een extra probleem voor de nieuwe democratische regeringen in Zuid-Amerika met hun nationale schulden aan Amerikaanse banken. De schukden namen dus toe, terwijl vaak tegelijkertijd de prijzen van exportartikelen daalden.

"This is where Friedman's crisis theory became self-reinforcing. The more the global economy followed his prescriptions, with floating interest rates, deregulated prices and export-oriented economies, the more crisis-prone the system became, producing more and more of precisely the type of melt-downs he had identified as the only circumstances under which governments would take more of his radical advice. In this way, crisis is built into the Chicago School model. When limitless sums of money are free to travel the globe at great speed, and speculators are able to bet on the value of everything from cocoa to currencies, the result is enormous volatility. And, since free-trade policies encourage poor countries to continue to rely on the export of raw resources such as coffee, copper, oil or wheat, they are particularly vulnerable to getting trapped in a vicious circle of continuing crisis. A sudden drop in the price of coffee sends entire economies into depression, which is then deepened by currency traders who, seeing a country's financial downturn, respond by betting against its currency, causing its value to plummet. When soaring interest rates are added, and national debts balloon overnight, you have a recipe for potential economic mayhem.

Chicago School believers tend to portray the mid-eighties onward as a smooth and triumphant victory march for their ideology: at the same time that countries were joining the democratic wave, they had the collective epiphany that free people and unfettered free markets go hand in hand. That epiphany was always fictional. What actually happened is that just as citizens were finally winning their long-denied freedoms, escaping the shock of the torture chambers under the likes of the Philippines' Ferdinand Marcos and Uruguay's Juan Maria Bordaberry, they were hit with a perfect storm of financial shocks - debt shocks, price shocks and currency shocks - created by the increasingly volatile, deregulated global economy."(159-160)

" Having finally escaped the darkness of dictatorship, few elected politicians were willing to risk inviting another round of U.S.-supported coups d'état by pushing the very policies that had provoked the coups of the seventies - especially when the military officials who had staged them were, for the most part, not in prison but, having negotiated immunity, in their barracks, watching. Understandably unwilling to go to war with the Washington institutions that owned their debts, crisis-struck new democracies had little choice but to play by Washington's rules. And then, in the early eighties, Washington's rules got a great deal stricter. That's because the debt shock coincided precisely, and not coincidentally, with a new era in North-South relations, one that would make military dictatorships largely unnecessary. It was the dawn of the era of 'structural adjustment' - otherwise known as the dictatorship of debt."(161)

Belangrijk in dit verband is ook dat de IMF en de World Bank in de VS gevestigd waren en dat veel medewerkers Amerikaanse economen uit de Chicago School waren.

"Friedman may have opposed the institutions on philosophical grounds, but practically, there were no institutions better positioned to implement his crisis theory. When countries were sent spiraling into crisis in the eighties, they had nowhere else to turn but the World Bank and the IMF. When they did, they hit a wall of orthodox Chicago Boys, trained to see their economic catastrophes not as problems to solve but as precious opportunities to leverage in order to secure a new free-market frontier. Crisis opportunism was now the guiding logic of the world's most powerful financial institutions. It was also a fundamental betrayal of their founding principles."(162)

"The colonization of the World Bank and the IMF by the Chicago School was a largely unspoken process, but it became official in 1989 when John Williamson unveiled what he called 'the Washington Consensus'. It was a list of economic policies that he said both institutions now considered the bare minimum for economic health —"the common core of wisdom embraced by all serious economists". These policies, masquerading as technical and uncontentious, included such bald ideological claims as all "state enterprises should be privatized" and "barriers impeding the entry of foreign firms should be abolished". When the list was complete, it made up nothing less than Friedman's neoliberal triumvirate of privatization, deregulation / free trade and drastic cuts to government spending. (...) When crisis-struck countries came to the IMF seeking debt relief and emergency loans, the fund responded with sweeping shock therapy programs, equivalent in scope to 'The Brick' drafted by the Chicago Boys for Pinochet and the 220-law decree cooked up in Goni's living room in Bolivia."(163)

Over Polen's Lech Walesa en de vrije vakbond Solidariteit in de 1980-er jaren.

"Tired of living in a country that worshipped an idealized working class but abused actual workers, Solidarity members denounced the corruption and brutality of the party functionaries who answered not to the people of Poland but to remote and isolated bureaucrats in Moscow. All the desire for democracy and self-determination suppressed by one-party rule was being poured into local Solidarity unions, sparking a mass exodus of members from the Communist Party."(172)

"Solidarity was forced underground, but during the eight years of police-state rule, the movement's legend only grew. In 1983, Walesa was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, although his activities were still restricted and he could not accept the prize in person."(174)

"By 1988, the terror of the initial crackdown had eased, and Polish workers were once again staging huge strikes. This time, with the economy in free fall, and the new, moderate regime of Mikhail Gorbachev in power in Moscow, the Communists gave in."(174)

En weer was er sprake van een economische crisissituatie:

"As Latin Americans had just learned, authoritarian regimes have a habit of embracing democracy at the precise moment when their economic projects are about to implode. Poland was no exception. The Communists had been mismanaging the economy for decades, making one disastrous, expensive mistake after another, and it was at the point of collapse. "To our misfortune, we have won!" Walesa famously (and prophetically) declared. When Solidarity took office, debt was $40 billion, inflation was at 600 percent, there were severe food shortages and a thriving black market. Many factories were making products that, with no buyers in sight, were destined to rot in warehouses. For Poles, the situation made for a cruel entry into democracy. Freedom had finally come, but few had the time or the inclination to celebrate because their paychecks were worthless. They spent their days lining up for flour and butter if there happened to be any in the stores that week."(175)

"But as had been the case in Latin America, before anything else could happen, Poland needed debt relief and some aid to get out of its immediate crisis. In theory, that's the central mandate of the IMF: providing stabilizing funds to prevent economic catastrophes. If any government deserved that kind of lifeline it was the one headed by Solidarity, which had just pulled off the Eastern Bloc's first democratic ouster of a Communist regime in four decades. Surely, after all the Cold War railing against totalitarianism behind the Iron Curtain, Poland's new rulers could have expected a little help. No such aid was on offer. Now in the grips of Chicago School economists, the IMF and the U.S. Treasury saw Poland's problems through the prism of the shock doctrine. An economic meltdown and a heavy debt load, compounded by the disorientation of rapid regime change, meant that Poland was in the perfect weakened position to accept a radical shock therapy program. And the financial stakes were even higher than in Latin America: Eastern Europe was untouched by Western capitalism, with no consumer market to speak of. All of its most precious assets were still owned by the state - prime candidates for privatization. The potential for rapid profits for those who got in first was tremendous."(176)

Jeffrey Sachs werd adviseur van de Poolse regering en Solidariteit. En daarmee werd de neolibrale koers ingezet.

"It was an even more radical course than the one imposed on Bolivia: in addition to eliminating price controls overnight and slashing subsidies, the Sachs Plan advocated selling off the state mines, shipyards and factories to the private sector. It was a direct clash with Solidarity's economic program of worker ownership, and though the movement's national leaders had stopped talking about the controversial ideas in that plan, they remained articles of faith for many Solidarity members. Sachs and Lipton wrote the plan for Poland's shock therapy transition in one night."(177)

" ... only two months after Poland announced that it would accept shock therapy, something happened that would change the course of history and invest Poland's experiment with global significance. In November 1989, the Berlin Wall was joyously dismantled, the city was turned into a festival of possibility and the MTV flag was planted in the rubble, as if East Berlin were the face of the moon. Suddenly it seemed that the whole world was living the same kind of fast-forward existence as the Poles: the Soviet Union was on the verge of breaking apart, apartheid in South Africa seemed on its last legs, authoritarian regimes continued to crumble in Latin America, Eastern Europe and Asia, and long wars were coming to an end from Namibia to Lebanon. Everywhere, old regimes were collapsing, and the new ones rising in their place had yet to take shape."(181-182)

"In 1989, history was taking an exhilarating turn, entering a period of genuine openness and possibility. So it was no coincidence that Fukuyama, from his perch at the State Department, chose precisely that moment to at tempt to slam the history book shut. Nor was it a coincidence that the World Bank and the IMF chose that same volatile year to unveil the Washington Consensus - a clear effort to halt all discussion and debate about any economic ideas outside the free-market lockbox. These were democracy-containment strategies, designed to undercut the kind of unscripted self-determination that was, and always had been, the greatest single threat to the Chicago School crusade."(184)

"Fukuyama had claimed that democratic and 'free market reforms' were a twin process, impossible to pry apart. Yet in China, the government had done precisely that: it was pushing hard to deregulate wages and prices and expand the reach of the market - but it was fiercely determined to resist calls for elections and civil liberties. The demonstrators, on the other hand, demanded democracy, but many opposed the government's moves toward unregulated capitalism, a fact largely left out of the coverage of the movement in the Western press. In China, democracy and Chicago School economics were not proceeding hand in hand; they were on opposite sides of the barricades surrounding Tiananmen Square."(184)

"Friedman's definition of freedom, in which political freedoms were incidental, even unnecessary, compared with the freedom of unrestricted commerce, conformed nicely with the vision taking shape in the Chinese Politburo. The party wanted to open the economy to private ownership and consumerism while maintaining its own grip on power—a plan that ensured that once the assets of the state were auctioned off, party officials and their relatives would snap up the best deals and be first in line for the biggest profits. According to this version of 'transition', the same people who controlled the state under Communism would control it under capitalism, while en joying a substantial upgrade in lifestyle. The model the Chinese government intended to emulate was not the United States but something much closer to Chile under Pinochet: free markets combined with authoritarian political control, enforced by iron-fisted repression. From the start, Deng clearly understood that repression would be crucial."(185)

"The demonstrations were not against economic reform per se; they were against the specific Friedmanite nature of the reforms—their speed, ruthlessness and the fact that the process was highly antidemocratic. "(187)

"There will never be reliable estimates for how many people were killed and injured in those days. The party admits to hundreds, and eyewitness reports at the time put the number of dead at between two thousand and seven thousand and the number of injured as high as thirty thousand. The protests were followed by a national witch hunt against all regime critics and opponents. Some forty thousand were arrested, thousands were jailed and many—possibly hundreds—were executed. As in Latin America, the government reserved its harshest repression for the factory workers, who represented the most direct threat to deregulated capitalism."(188)

"It was this wave of reforms that turned China into the sweatshop of the world, the preferred location for contract factories for virtually every multinational on the planet. No country offered more lucrative conditions than China: low taxes and tariffs, corruptible officials and, most of all, a plentiful low-wage workforce that, for many years, would be unwilling to risk demanding decent salaries or the most basic workplace protections for fear of the most violent reprisals. For foreign investors and the party, it has been a win-win arrangement. According to a 2006 study, 90 percent of China's billionaires (calculated in Chinese yuan) are the children of Communist Party officials. Roughly twenty-nine hundred of these party scions - known as 'the princelings' - control $260 billion. It is a mirror of the corporatist state first pioneered in Chile under Pinochet: a revolving door between corporate and political elites who combine their power to eliminate workers as an organized political force. "(190)

Over het Freedom Charter van 1955 van het ANC.

"The charter enshrines the right to work, to decent housing, to freedom of thought, and, most radically, to a share in the wealth of the richest country in Africa, containing, among other treasures, the largest goldfield in the world."(196)

"What was taken as a given by all factions of the liberation struggle was that apartheid was not only a political system regulating who was allowed to vote and move freely. It was also an economic system that used racism to enforce a highly lucrative arrangement: a small white elite had been able to amass enormous profits from South Africa's mines, farms and factories because a large black majority was prevented from owning land and forced to provide its labor for far less than it was worth—and was beaten and imprisoned when it dared to rebel. In the mines, whites were paid up to ten times more than blacks, and, as in Latin America, the large industrialists worked closely with the military to have unruly workers disappeared."(196)

"Since there was already widespread agreement that corporations shared responsibility for the crimes of apartheid, the stage was set for Mandela to explain why key sectors of South Africa's economy needed to be nationalized just as the Freedom Charter demanded. He could have used the same argument to explain why the debt accumulated under apartheid was an illegitimate burden to place on any new, popularly elected government. There would have been plenty of outrage from the IMF, the U.S. Treasury and the European Union in the face of such undisciplined behavior, but Mandela was also a living saint - there would have been enormous popular support for it as well. We will never know which of these forces would have proved more powerful. In the years that passed between Mandela's writing his note from prison and the ANC's 1994 election sweep in which he was elected president, something happened to convince the party hierarchy that it could not use its grassroots prestige to reclaim and redistribute the country's stolen wealth. So, rather than meeting in the middle between California and the Congo, the ANC adopted policies that exploded both inequality and crime to such a degree that South Africa's divide is now closer to Beverly Hills and Baghdad. Today, the country stands as a living testament to what happens when economic reform is severed from political transformation. Politically, its people have the right to vote, civil liberties and majority rule. Yet economically, South Africa has surpassed Brazil as the most unequal society in the world."(198)

In het overleg na 1994 won het ANC politiek gezien op alle punten. Maar op economisch vlak slaagde De Klerk's NP erin het economisch beleid op het spoor van de Washington Consensus van IMF en World Bank te krijgen. Daarmee werd het vrijwel onmogelijk het beleid uit te voeren dat het ANC politiek gezien zo graag wilde.

"But, in a familiar story, weighed down by debt and under international pressure to privatize these services, the government soon began raising prices. After a decade of ANC rule, millions of people had been cut off from newly connected water and electricity because they couldn't pay the bills. At least 40 percent of the new phones lines were no longer in service by 2003. As for the 'banks, mines and monopoly industry' that Mandela had pledged to nationalize, they remained firmly in the hands of the same four white-owned megaconglomerates that also control 80 percent of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. In 2005, only 4 percent of the companies listed on the exchange were owned or controlled by blacks. Seventy percent of South Africa's land, in 2006, was still monopolized by whites, who are just 10 percent of the population. Most distressingly, the ANC government has spent far more time denying the severity of the AIDS crisis than getting lifesaving drugs to the approximately 5 million people infected with HIV, though there were, by early 2007, some positive signs of progress. Perhaps the most striking statistic is this one: since 1990, the year Mandela left prison, the average life expectancy for South Africans has dropped by thirteen years."(206)

"Of all the constraints on the new government, it was the market that proved most confining—and this, in a way, is the genius of unfettered capitalism: it's self-enforcing. Once countries have opened themselves up to the global market's temperamental moods, any departure from Chicago School orthodoxy is instantly punished by traders in New York and London who bet against the offending country's currency, causing a deeper crisis and the need for more loans, with more conditions attached."(207)

"Mbeki convinced Mandela that what was needed was a definitive break with the past. The ANC needed a completely new economic plan - something bold, something shocking, something that would communicate, in the broad, dramatic strokes the market understood, that the ANC was ready to embrace the Washington Consensus. (...) In June 1996, Mbeki unveiled the results: it was a neoliberal shock therapy program for South Africa, calling for more privatization, cutbacks to government spending, labor 'flexibility', freer trade and even looser controls on money flows."(209)

"The fact that the ANC dismissed the Commission's call for corporate reparations is particularly unfair, Sooka pointed out, because the government continues to pay the apartheid debt."(211)

"In the end, South Africa has wound up with a twisted case of reparations in reverse, with the white businesses that reaped enormous profits from black labor during the apartheid years paying not a cent in reparations, but the victims of apartheid continuing to send large paychecks to their former victimizers. And how do they raise the money for this generosity? By stripping the state of its assets through privatization—a modern form of the very looting that the ANC had been so intent on avoiding when it agreed to negotiations, hoping to prevent a repeat of Mozambique. Unlike what happened in Mozambique, however, where civil servants broke machinery, stuffed their pockets and then fled, in South Africa the dismantling of the state and the pillaging of its coffers continue to this day."(213)

Over Rusland na de val van de muur in 1989 en onder Gorbatsjov.

"By the beginning of the nineties, with his twin policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroïka (restructuring), Gorbachev had led the Soviet Union through a remarkable process of democratization: the press had been freed, Russia's parliament, local councils, president and vice president had been elected, and the constitutional court was independent. As for the economy, Gorbachev was moving toward a mixture of a free market and a strong safetynet, with key industries under public control - a process he predicted would take ten to fifteen years to be completed. His end goal was to build social democracy on the Scandinavian model, "a socialist beacon for all mankind"."(219)

Maar Gorbatsjov kreeg geen internationale econmische steun als hij niet ook overging tot de neoliberale shocktherapie.

"So what happened at the G7 meeting in 1991 was totally unexpected. The nearly unanimous message that Gorbachev received from his fellow heads of state was that, if he did not embrace radical economic shock therapy immediately, they would sever the rope and let him fall. "Their suggestions as to the tempo and methods of transition were astonishing," Gorbachev wrote of the event. Poland had just completed its first round of shock therapy under the IMF's and Jeffrey Sachs's tutelage, and the consensus among British prime minister John Major, U.S. president George H. W. Bush, Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney and Japanese prime minister Toshiki Kaifu was that the Soviet Union had to follow Poland's lead on an even faster timetable. After the meeting, Gorbachev got the same marching orders from the IMF, the World Bank and every other major lending institution. Later that year, when Russia asked for debt forgiveness to weather a catastrophic economic crisis, the stern answer was that the debts had to be honored. (...)